After spending far too much time recently searching through the British Newspaper Archives, today I am launching a new series on the blog called "Newcastle Narratives" which will feature stories I have uncovered about my family members that were living in Newcastle during the Victorian era and their many escapades that often seem to be straight out of a Dickens novel. Up first is a story about James Charles Breem (1846-1883), the brother to my 3x great grandmother Jane Ann, who had his pigeons stolen from the family's backyard. While this story is periphery to my direct line of ancestors, it has provided me with fascinating insight into the Breem family and the household in which Jane Ann grew up.

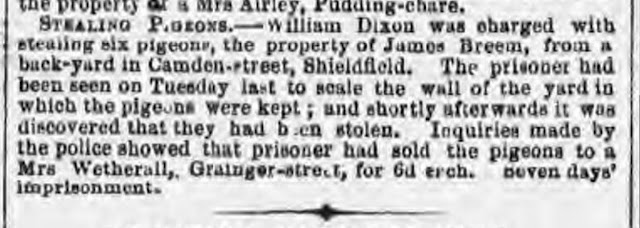

The first newspaper clipping I found that mentions the events was published in the Newcastle Courant's "Police Intelligence" column on March 29, 1861 and describes how the thief climbed over the wall into the family's yard and sold the pigeons for a sixpence (about £2.29 in today's currency) each to a shopkeeper on Grainger Street. He was convicted and sentenced to seven days in prision.

While this photo is taken 100 years later in Aldwark, York, the structure on the left of the image gives a good idea of what a pigeon loft would look like in the backyard of a working class family home. It is likely that James would have built something similar to house his pigeons and that the pigeon cote would have taken up most of the space in their cramped city backyard. In the north of England, "the wooden pigeon lofts, often made from waste timber and painted brightly to attract the birds, formed a distinctive feature of the landscape." (Johnes, 361)

The second story I found while searching the newspaper archives was published in the The Newcastle Guardian on March 30, 1861. The column titled "Newcastle Police Court" provided additional information about the case including that it heard on a Thursday before the same magistrate as the day before, Ald. Dodds and Sillick. This account of the event differs in a few key facts: the family's house is listed as being on Franklin Street rather than Camden Street, Mrs. Wetherall morphs into Mr. Weatherill, and in this clipping James is credited with finding the birds rather than the police investigation tracking down the suspect.

While largely impossible to determine which article is more truthful, census records can provide a few clues. The same year that the bird snatching occurred, a UK census was held. James, then 15 years old is listed as living with his step-mother Ann, brother Robert, and sister Jane Ann (my 3x great grandmother). Their father, John Charles, is not recorded with the family as he is enumerated in harbour in London on board the ship Hudgill, which he captained for many years traveling coasting routes transporting coal shipments from the mines near Newcastle. James is working as a coal miner's clerk, a first step towards his future career as an accountant. The family's address is listed as 14 Camden Street leading me to believe that the address given by the first newspaper article in the Newcastle Courant is more factually accurate than the Franklin Street address provided in the second clipping from The Newcastle Guardian.

This map of Newcastle from 1864, just three years after the pigeon incident, shows the location of both Camden Street and Franklin Street within a few blocks of each other in the Shieldfield neighbourhood of Newcastle. The full map is available at Newcastle Collection to situate the location of Shieldfield within Newcastle more broadly.

A description of the neighbourhood in 1807 published by D. Akenhead and Sons in "The Picture of Newcastle Upon Tyne Containing a Guide to the Town & Neighbourhood, an Account of the Roman Wall, and a Description of the Coal Mines" reports on Shieldfield as follows: "At the further end a steep hill with houses on one side, called Pandon Bank, ascending which, and keeping to the left, you reach Pleasant Row and Shield Field, two ranges of very good houses in an airy and elevated situation, a little out of town."

In 1827, another report of Newcastle described how houses in Shieldfield had gardens behind, as evidenced in the reports of the pigeons being kept in the Breem's yard. The report writes: "Fronting the east, there is a row of good houses, very properly styled Pleasant Row, beyond which is another, named Shield Field, from the ground on which it stands. These houses command an agreeable prospect, have a range of beautiful gardens behind, and are, in every respect, very convenient as a retreat for men of business."

|

| Kent Street via the Newcastle Libraries Flicker page. |

However, by the time James Breem had his pigeons stolen from the backyard in 1861, Shieldfield was experiencing rapid population expansion. A comparison of maps from the time period show how the city was growing quickly out into former suburbs bringing with it larger numbers of working class residents and more cramped living conditions. This picture from Newcastle Libraries depicting Kent Street, one of the five streets within the same area as Camden Street and Franklin Street, shows what the front of the typical row houses looked in the period.

After reading these newspaper clippings, I was immediately curious why James would have been keeping pigeons in his backyard. The fact that one of the articles indicate that he was able to recognize his birds in another shop leads me to believe that he had an attachment to them that went beyond just raising them as meat birds (although I have watched enough of Mrs. Crocombe's cooking videos on English Heritage's YouTube channel to know that pigeon pie is not just a nursery rhyme creation!). Furthermore, the fact that they were not immediately butchered upon being stolen or sold, makes me believe that they were bought by the Weatheralls for another purpose. A quick Google search brought up an article titled "Pigeon Racing and Working-Class Culture in Britain, c. 1870-1950" by Martin Johnes which was published in Social History, Volume 4, Issue 3.

While reading the article I was fascinated to learn that pigeon keeping and pigeon racing was extremely popular throughout the Victorian era and into the 20th century particularly in working class mining communities in the north of England such as Newcastle. The article details how "in the 1760s pigeon fancying – keeping birds for their aesthetic and intellectual appeal – became quite common amongst the leisured class. . . . [and] in the 1840s and 1850s the rapid growth of the telegraph led to a decline in the use of pigeons for messages and some birds owned by merchant and press agencies came onto the open market, leading to the growth of pigeon racing amongst individuals" (Johnes, pages 362-363) including those of lower classes who could not previously afford to participate in pigeon keeping. Local communities would hold pigeon races on Sundays and "birds were trained to fly back to their lofts at a low height, sometimes never higher than six feet, in order to maximize their speed over races that could be as short as a mile. Each pigeon was marked by ink for identification and, after reaching its loft, its owner had to take it to the race headquarters, usually an inn, with the first bird there being declared the winner. Inequalities in the location of lofts could be equalized by forcing owners to draw lots for where their birds were released from." (Johnes, 363) The article goes on to describe how pigeon racing was linked to tensions in respectability and capitalism in the time period.

While I can't prove that James Charles Breem kept his pigeons for this purpose, it is certainly a plausible hypothesis given the story told in the newspaper clippings. Six years later in August 1867, James married Ann Hunter, the only daughter of a veterinary surgeon. Perhaps his love of pigeons led to them crossing paths... it is pure speculation, but I can imagine that the local vet could have run in the same circles as a young pigeon fancier.

After reading these newspaper clippings, I was immediately curious why James would have been keeping pigeons in his backyard. The fact that one of the articles indicate that he was able to recognize his birds in another shop leads me to believe that he had an attachment to them that went beyond just raising them as meat birds (although I have watched enough of Mrs. Crocombe's cooking videos on English Heritage's YouTube channel to know that pigeon pie is not just a nursery rhyme creation!). Furthermore, the fact that they were not immediately butchered upon being stolen or sold, makes me believe that they were bought by the Weatheralls for another purpose. A quick Google search brought up an article titled "Pigeon Racing and Working-Class Culture in Britain, c. 1870-1950" by Martin Johnes which was published in Social History, Volume 4, Issue 3.

|

| A cabinet card photographed by C. A. Solomons of Watford showing two Victorian-era men with their racing pigeons. |

While I can't prove that James Charles Breem kept his pigeons for this purpose, it is certainly a plausible hypothesis given the story told in the newspaper clippings. Six years later in August 1867, James married Ann Hunter, the only daughter of a veterinary surgeon. Perhaps his love of pigeons led to them crossing paths... it is pure speculation, but I can imagine that the local vet could have run in the same circles as a young pigeon fancier.

|

| Pigeon racing in Victorian England circa 1870. |

No comments:

Post a Comment